After you lose your mother, Mother’s Day becomes a somber day of reflection. Our mother is gone 21 years now. She died from lung cancer at the age of 56–a year younger than I am today. It was strange for me when I realized I’m older than my mother would ever be. Still, I reflexively reach for my phone to call her whenever something good or bad happens. Then, remind myself, with phone in hand, she’s not on the other end.

After you lose your mother, Mother’s Day becomes a somber day of reflection. Our mother is gone 21 years now. She died from lung cancer at the age of 56–a year younger than I am today. It was strange for me when I realized I’m older than my mother would ever be. Still, I reflexively reach for my phone to call her whenever something good or bad happens. Then, remind myself, with phone in hand, she’s not on the other end.

Her life was brief, but the life lessons she instilled in her three girls come back to us constantly. Sometimes, her lessons come slowly, subtly, and, other times, they slap us right in the face. I cannot express how much I love when that happens. Belonging to an Irish Catholic family, living in the Bronx, my mother was the eldest of six. Her life was filled with a steady stream of laundry–much of it done by hand. So, when she married, she insisted on squeezing a washer and a dryer into our already cramped kitchen. It would finally free her of the laborious chores of her childhood.

When I was 11, our parents separated. My mom, two sisters, and I would spend many years in our kitchen talking over the vibrational whir of the washer and the thunderous tumbling of the dryer. At dinnertime, she’d stop the machines mid-cycle so we could have some quiet conversation. Even after working twelve hours a day, six days a week, our mom always made time to sit at the kitchen table and ask about our day. The image of her reaching over to pull open the dryer door, without getting out of her chair, is forever etched in my memories.

Right there, in our groovy 70s kitchen with its loud orange and yellow geometric, metallic wallpaper and knock-off Saarinen white-round table with matching bucket chairs, hung a print of Picasso’s Bouquet of Peace. Since I was, as my mom would say, ‘the artistic one,’ I had trouble with the drawing’s simplicity. I mean, I was 12 and could draw a more lifelike image of a bouquet of flowers. It perplexed me as much as it intrigued me. As a teen, I found myself researching Pablo Picasso and the phases of his work. His earlier work was spot-on realistic. So, clearly, he knew how to draw and paint, but the influences of the time, lead him to break free from realism and delve into cubism, and, eventually, he turned to painting in a childlike manner. I also learned he painted The Bouquet of Peace in response to the peace demonstrations taking place in Stockholm in 1958.

Our kitchen table was the roundtable of our world. Under the watchful eye of The Bouquet of Peace, it’s where our single bra-burning, bellbottom-wearing, liberal-leaning mother created a safe space for her three girls to talk about anything and everything. Nothing was off-limits. It’s where she celebrated our rite of passage into womanhood, and, subsequently, where we complained about our cramps and pimples. It’s where we learned to put on makeup. It’s where we cried over boys. It’s where we talked about our mother’s limited paycheck and how, if we wanted a new pair of Jordache jeans or a new pair of Candies, we had to work for it.

Our kitchen table was the roundtable of our world. Under the watchful eye of The Bouquet of Peace, it’s where our single bra-burning, bellbottom-wearing, liberal-leaning mother created a safe space for her three girls to talk about anything and everything. Nothing was off-limits. It’s where she celebrated our rite of passage into womanhood, and, subsequently, where we complained about our cramps and pimples. It’s where we learned to put on makeup. It’s where we cried over boys. It’s where we talked about our mother’s limited paycheck and how, if we wanted a new pair of Jordache jeans or a new pair of Candies, we had to work for it.

The response to a piece of artwork is typically an emotional one–even if it’s no response at all. Picasso’s flowers were always waiting to greet me in the morning. I’d stare at it while eating my Cheerios. My mother loved the cheerful nature of it and how it represented a sweet gesture of one person giving to another. She shared with me how the giving of something as simple as a bouquet of flowers could bring much joy to the recipient. In those moments, my mother was teaching us the art of the giving, the art of simple beauty, and the art of appreciating art.

So, when I noticed my sister hung that very painting in her laundry room, it bothered me. Why would she choose to hang a significant piece from our childhood in such an obscure place? Then…BAM!!! It hit me. My sister got it right. It was the perfect place, right next to the whoosh of washer and the melodic tumbling of the dryer. Like I said, I love when that happens.

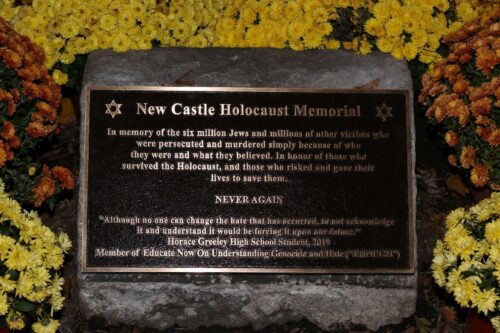

Ali began to focus her efforts on making an impact on the community and the schools. She wanted to find a way to increase Holocaust education for the next generation so that they could feel empowered to prevent this from ever happening again.

Ali began to focus her efforts on making an impact on the community and the schools. She wanted to find a way to increase Holocaust education for the next generation so that they could feel empowered to prevent this from ever happening again.

Holocaust survivor Peter Somogyi offered the keynote address which conveyed the pain and horror he endured as a victim of Dr. Mengele’s cruel experiments. A candle lighting ceremony was led by survivors and also by students of E.N.O.U.G.H.

Holocaust survivor Peter Somogyi offered the keynote address which conveyed the pain and horror he endured as a victim of Dr. Mengele’s cruel experiments. A candle lighting ceremony was led by survivors and also by students of E.N.O.U.G.H.