The holiday season is rapidly approaching, and with it, the Jewish festival of Hanukkah, an eight-day celebration honoring the triumph of the Jewish people over the Syrian Greeks. The holiday is joyous, complete with gift giving, dreidel spinning, menorah lighting and lots of latkes.

For me, however, a teacher trip through the Holocaust and Human Rights Education Center (HHREC) to Germany and Poland last summer caused a subtle shift in the way I think about Hanukkah and my career as an educator.

As a social studies teacher and self-proclaimed history nerd, I wanted to learn about this dark period in human history up close and bring these experiences back to my classroom. I can listen and read and even watch Ken Burns’ excellent documentary, “The US and the Holocaust”, but none of this makes history come alive the way walking along the streets of Berlin, Warsaw and Krakow did. It was here that I saw the physical evidence of a once thriving Jewish life, now all but gone. I walked in the very places where the Warsaw ghetto confined its Jewish residents. I visited concentration camps, like Auschwitz-Birkenau where millions were murdered and left with the picture of a pair of shoes that had once belonged to a small child seared in my mind.

Memory became paramount on this trip, as I scrambled to imprint every lecture we heard, every object we saw, and every place we visited into my consciousness. Our tour guide at Auschwitz, a Polish Professor and activist, reminded us that the simple act of visiting the death camp had afforded us the chance to bear witness to this evil tragedy and therefore we now shouldered the responsibility to make sure the next generation remembers. This has never been so important as it is today when Shoah survivors are diminishing in number.

This is where teachers come in.

As educators we make content choices. While a curriculum is prescribed in broad strokes, it is the teacher who decides to spend a week on World War II, and two days on the Cold War. Or vice versa. In so many ways we are the gatekeepers of history, and as such we have a responsibility to continually learn and consider how we will present material to our students.

As much as we want history to come alive for our students, we need to make it vibrant for ourselves. When we learn, they learn, and if there is a personal connection to the material all the better. I certainly cannot arrange for a field trip to Europe for my students, but I am certain when we find ourselves in our World War II unit next spring, there will be an increased interest because I can offer a personal lens with which they can view and understand this time period.

I hope that my enthusiasm will be palpable as I show them the photo of their English teacher and me straddling the wall with one foot in the former East Berlin and one foot in the West. I am excited to answer their questions as they look through the 100-page photo journal I created to try and capture the essence of my experience.

There are even pedagogical ideas from the trip–the idea of memorializing, the purpose of museums, the contrast with how our nation and Germany grapples with its dark history that have easily fit into our earlier units of study. In essence, the trip has rooted itself in my consciousness as a teacher, a Jewish adult and as a human.

My students remind me daily of my responsibility to help them develop compassion, empathy, and an ability to grapple with the darker side of human history. As for me, I will continue to celebrate the triumph of the Maccabees, and admire the warmth and light the menorah brings into my home. But my lens has shifted ever so slightly and I can never look at it in quite the same way. The on-going struggle of the Jewish people, which so many ethnic and racial groups experience is built into the story of Hanukkah, and this year I will light the candles and say the blessings for the six million European Jews who cannot.

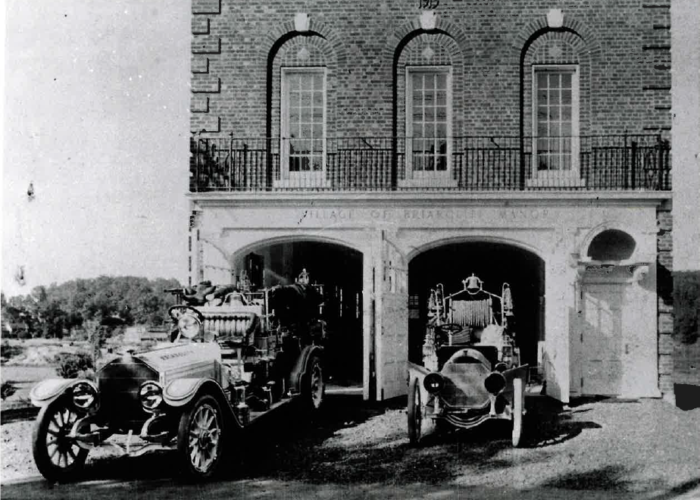

Founded in 1966, the New Castle Historical Society (NCHS) is a non-profit educational organization that seeks to research, discover, collect, and preserve the history of the Town of New Castle. The NCHS is located in the Horace Greeley House and is open to the public for tours and research.

Founded in 1966, the New Castle Historical Society (NCHS) is a non-profit educational organization that seeks to research, discover, collect, and preserve the history of the Town of New Castle. The NCHS is located in the Horace Greeley House and is open to the public for tours and research.