For perhaps more than 100 years, Civil War veterans William Freeland and Albert Ransom were buried in anonymity, their tombstones in the cemetery of St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church in Armonk either damaged and unreadable or, in Ransom’s case, missing altogether. But thanks to the efforts of a 93-year-old North Castle resident, and the help of an Armonk priest, both men now rest under newly-installed gravestones issued by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

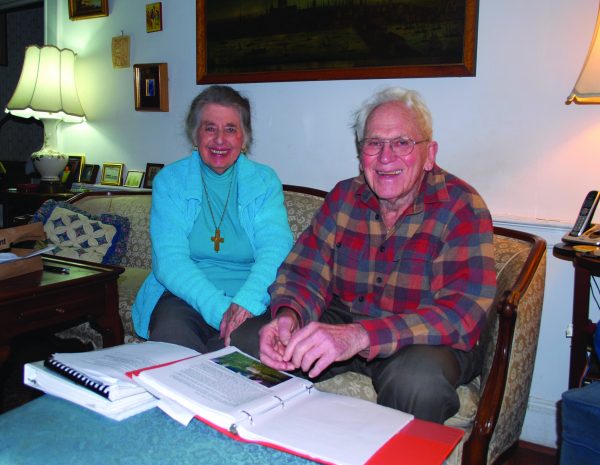

George Pouder, a 48-year North Castle resident who lives near the town’s border with Bedford, first began researching the cemeteries of Armonk ten years ago. A longtime member of the North Castle Historical Society, Pouder joined fellow society member Barbara Massi in a project documenting the burial grounds in Armonk.

“It was supposed to last three months, and it took three years,” Pouder recalls. The project, which resulted in a 166-page report, built on the research of former town historian Dick Lander. “We had a lot of fun doing it, and we found things that [Lander] hadn’t found, which was very unusual.”

During his research with Massi, Pouder took note of how many Civil War veterans are buried in the hamlet.

“I got interested in the Civil War soldiers. It really grabbed me and I couldn’t let go,” says Pouder. His own experience in WWII “made me feel like I had a kinship with these people. I didn’t want them to stay unknown and mute when nobody would know anything that they did.”

In February of 2015, Pouder published biographies on more than 100 Civil War soldiers, sailors, and spouses. Two of the soldiers profiled were Freeland, an Army Private, and Ransom, a Corporal who was captured by Confederate forces and held as a prisoner of war at Andersonville Prison in Georgia. Upon seeing the condition of Freeland’s tombstone – which was smashed and facedown – Pouder began fighting for a new stone Freeland, who died of typhoid at the age of 23.

“The VA, in their infinite wisdom, said, ‘Well he has a stone already,” says Pouder, who countered that the stone was facedown and unreadable. In his biography of Freeland, Pouder even offers to dig the grave himself – though ultimately it didn’t come to that.

Applying for the stones was complicated by the fact that the VA would only accept an application on behalf of the cemetery’s custodian. St. Stephen’s was without a full-time priest until January 2015, when Rev. Nils Chittenden moved into the Rectory. Chittenden worked with Pouder to obtain the necessary records and to fill out the applications.

“The VA demands, I guess for good reason, a very high burden of proof of the story of these particular people,” explains Chittenden. “They want documentation about the years they were in the army, documentation about their birth and their death dates, and documentation to prove that they are definitely buried there.”

In Ransom’s case, since there was no stone, it was also not completely clear where his burial site was located. “So [the VA] said, ‘Oh, no dice,’” recalls Pouder. Finally, they dug up a map with Ransom’s plot listed.

“As George’s priest, I wanted to really support him in this endeavor, because it is such a good thing that George is doing,” says Chittenden, whose father served the British Army in WWII. “But also I feel passionately that people who gave so much to the country, who suffered so greatly, and whose family suffered so greatly for what they did, be given that sort of recognition and remembrance.”

Installed in October, the tombstones were officially dedicated on Veterans Day.

Pouder, who grew up in New Rochelle and owned Lieb’s Nursey in the city before retiring 23 years ago, has been a member of the historical society since moving to North Castle; before moving, he had been a member of the New Rochelle Historical Society. His wife, Aurelia, was a member of the History Hounds, a group that met to discuss historical topics. Even the couple’s house is historic; dating back to 1778, only its remote location saved it during the British burning of Bedford during the Revolutionary War.

Along with his publication on the Civil War veterans and his project with Massi on Armonk’s burial grounds, Pouder worked with fellow Historical Society member Nicholas Cerullo on a report about how the town’s residents responded to President Lincoln’s call for draftees during the Civil War. The projects are all available at the North Castle Public Library. Pouder stresses that he has never sought to make money from the projects. “It would be very unlikely that anyone would buy it,” he says. With Ransom and Freeland no longer buried in anonymity, Pouder’s work has already paid off.

Andrew Vitelli is a Westchester native and the editor of Inside Armonk magazine.

The stories told will focus on people who served in the U.S. military, particularly during the Civil War. Tour-goers will visit the gravesites of two veterans of the Civil War, U.S. Army Private William Freeland and Corp. Albert Ransom.

The stories told will focus on people who served in the U.S. military, particularly during the Civil War. Tour-goers will visit the gravesites of two veterans of the Civil War, U.S. Army Private William Freeland and Corp. Albert Ransom.