By Matt Smith

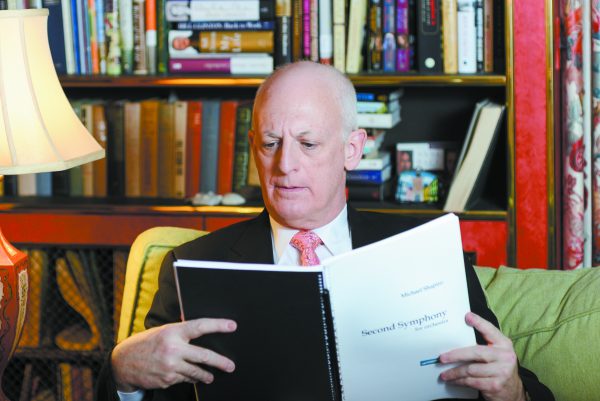

“The qualities that make a good conductor are, of course, a good ear, knowledge of the score, technical ability (hands, baton), a deep knowledge of all the instruments in the orchestra, and an ability to lead,” explains David Leibowitz, Conductor and Music Director of the New York Repertory Orchestra. “A great conductor has all these, but also that extra ingredient–a strong vision of how a piece of music should sound and how to convey that vision to the players.”

“That is what Michael has,” he continues. “He knows what he wants and he gets it. More important, he doesn’t stop until he gets it.” The “Michael” to which he refers is, of course, Michael Shapiro, world-renowned composer and conductor–and current music director and conductor of New Castle’s very own Chappaqua Orchestra.

Born and bred in Brooklyn, New York, Shapiro prides himself on his strong connection to music, and a strong passion for all types of the art form–something he presumably inherited from his father, a Klezmer band clarinetist who himself was “involved in all different forms of music.” In particular, “he loved swing jazz,” says Shapiro. “And through him [and his connections], I was able to hear some of the greats–like Louis Armstrong–live in concert, when I was a child. [I was] very lucky to grow up [in the business] and go to concerts continually, which has been a tremendous influence on me.”

Enjoying “the greats” set off a spark in little, seven-year-old Shapiro, who soon after developed his own interest in music. And he has since “done music all my life.” And indeed, throughout his career, Shapiro has conducted “literally all over the country,” working with such orchestras as the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra in the UK, Houston Symphony Orchestra, Virginia Symphony Orchestra, Charleston Symphony Orchestra, West Point Band’s The Jazz Knights, Traverse Symphony Orchestra, Garden State Philharmonic, Opera Theatre of Northern Virginia, and the Dallas Winds Symphony, to name a few.

He has also worked at a worldwide level, serving as vocal coach and assistant conductor at the Zurich Opera Studio in Zurich, Switzerland; as music consultant to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington D. C., and as composer-in-residence at the Cabrillo Festival of Contemporary Music, where his original orchestral composition, Roller Coaster, received its West Coast premiere. Furthermore, he has also composed incidental music for Dateline NBC.

Of course, since 2002, Shapiro has served as music director and conductor of The Chappaqua Orchestra. Since beginning with the organization, which he notes “brought [him] back to conducting really fiercely,” he prides himself on taking the group “from one point to the other and making it a [more vibrant] presence in the culture of our town” He notes that under his tutelage, the orchestra has performed “all kinds of different literature…[and] is now very close to being an all-professional orchestra of the highest quality.”

And he’s not just tooting his own horn–or rather, waving his own baton; others think so, too. In fact, it’s well documented that under Shapiro’s leadership, the Chappaqua Orchestra has successfully “reached new artistic heights” in the last 14 years. Additionally, to his credit, the April 2006 performance of the Verdi Requiem,

conducted by Shapiro and performed in collaboration with the Taconic Opera, was even deemed the “musical event of the decade” in Westchester.

And if all that wasn’t enough, when he’s not conducting an orchestra, you’ll find him conducting business: “I’ve been involved in real estate for many years,” he shares. He’s also a bestselling author; one of his books, The Jewish 100, was, in fact, a New York Times bestseller and has since been translated into eight languages, include Chinese, Japanese, Portuguese and Russian, since its release in 1994 (Note: An updated edition was released more recently, in 2012). “And I love sports,” he says. “Particularly golf…I’m a golfer. And I love basketball [and] being tortured by the New York Knicks.”

He also enjoys spending time with his kids, and learning about music from them too. “My daughter loves rock music of the 60’s and early ’70’s,” he shares, with a laugh, “and she’s remarked how I know so little about it…because back then, in those days, I was listening to Brahms.”

Above all, however, he thanks partner Marjorie Perlin, for her insurmountable love and support. “[She’s] the most supportive person in my life,” he says. “She’s the best listener and the best critic. Her support has been completely total and has been a tremendous help in getting me to even higher levels, not only [in terms] of performance, but [in terms of] my own musical standards.”

So, given all of his present success, where does Shapiro see himself professionally in the next five years? He answers first, quite simply, “Doing the same, but in more prominent venues.”

“I’m always pushing the envelope as much as I can, and trying to get bigger and better performances,” he continues. “I’m really looking forward to writing more pieces for the theatre, either incidental music or ballet, and certainly [more] opera.”

Shapiro also seems to have a good sense of what is really important in terms of the art form. “The great performances and standing ovations and all the rest of those things are wonderful,” he explains, “but….working with fantastic, high-quality performers and producing works that you’re proud of [no matter what the result]… that’s what counts.” Shapiro recalls one such “massive” standing ovation at a concert this past January at Meyerson Symphony Center in Dallas, Texas. “That [standing ovation] doesn’t often happen,” he states, with a smile, “so, when it does, it’s just amazing.”

So, considering such successes, when was the first time he knew he had “made it” as a musician? Ever so humble, he chuckled as he responded: “I’m still trying to make it.”

However, he does recall the “first major big performance” he gave–“when I knew I had something good,” he notes–at Westchester County Center in front of 2,000 people. “It was a commission by the now-defunct Philharmonic Symphony of Westchester” to compose music for narrator and orchestra to accompany a recitation of the signing of the Declaration of Independence–when he was just 25 years old.

“[The] piece premiered during the Bicentennial, so it was a big [deal],” Shapiro explains. “And [it] was narrated by José Ferrer, who won the Academy Award for Cyrano de Bergerac. The great pianist Van Cliburn was also on the program…so [these were] famous people [I was dealing with]. It was a great thrill for me to be around them and have that [experience].”

And as to how he has arrived to his current stature, Shapiro credits rigorous training. The first of his music teachers was Consuelo Elsa Clark, with whom he studied in Rockville Centre. “Miss Clark was an amazingly great teacher,” he shares. “And she came from a very strong tradition. It was great learning from her.”

From there, he went on to study conducting with Carl Bamberger at the Mannes College of Music (“and much later at Bard College with Harold Farberman,” he notes). “I also studied with other composers–Vincent Persichetti was a major influence. Sir Malcolm Arnold, too, [I studied with] briefly.”

Shapiro’s “most influential” composition teacher, however, was famed American composer Elie Siegmeister, with whom he studied privately “and rigorously,” for four years, while attending classes at Columbia and Juilliard, the latter where he eventually earned his master’s degree.

And of course, there was his score reading and ear training teacher, Mme. Renée Longy, known to generations of Julliard students, due to her rigorous demands, as “the infamous madame of dictation.” “She was extraordinarily difficult,” Shapiro confesses, honestly, “but ultimately, [a] very loving teacher.” In fact, Longy’s techniques proved to be so beneficial in the long run that Shapiro admits, “I still use [them] to this day when I conduct an orchestra.”

To that end, on the subject of teaching and further developing upon what one learns in school, Shapiro notes that once he discovered he had the musical talent, and enjoyed playing instruments, there was no question he’d pursue it full time:

“It’s like eating. When you’re hungry, you need to eat,” he says. “It’s the same way with music…It’s just a feeling… something you respond to… like anything else. You have a talent in it, you [pursue it].” “And then,” he adds, with a wink, “if you’re smart, you get the right teachers.”

Furthermore, to aspiring musicians, he advises: “keep your head down and just go to work,” he says, emphasizing that one should not compare him or herself to anyone else or their path. “And never stop reading. Or listening,” he advises. “Even at my stage, having [conducted] as long as I have, I’m always teaching myself by watching and listening to what others have done.”

His colleagues echo Shapiro’s advice, as many have continued to hone their skills through watching him work. “Michael cares deeply and fully about the art of music,” comments David Leibowitz, of the aforementioned New York Repertory Orchestra. “He is never anything less than 100% committed to [his] music–whether in performance or composing, or in just discussing what he likes and doesn’t like about a [particular] piece of music or performer. [Additionally], he has a very definite point of view [about what music should or shouldn’t be] and [he] argues his case well.”

Shapiro explains his art further: “Conducting is really listening [and] hearing to an extremely high level. [It’s about] manipulating the sound orally and not necessarily in words or in thoughts. To be a true composer, you need to compose every day [and] that means every day. To be a true conductor, you need to know your scores better than the individual players in the orchestra or band know their parts. The depth of knowledge has to be total, in the fullest sense of the word.”

But while he’s indeed adamant about one putting their nose to the grindstone, he also stresses the importance of letting loose and thinking creatively. “Without the creative [element] at the highest possible level, you can’t really do a fine job from a professional standpoint,” he says. “It all has to–and should–work together. You can’t really have one without the other.”

As a master composer at both the creative and professional level, Shapiro recognizes the value of music within a given community. He states, “Music [says] something [in a way] that words can’t. It’s ethereal, and that’s what makes it special. Music can lift us up to a different place. It can really move the spirit like nothing else.” And, having spent 40 years in the business, Shapiro obviously knows, and has witnessed, the power of music firsthand. Given this, when he composes, he draws inspirations from the great musicians of the past–musicians whose music moved his spirit in the same way as he describes. Stephen Foster, John Philip Sousa, Charles Ives, and George Gershwin are among those who influence Shapiro and his work. “As a kid, too,” he continues, “I was very influenced by [pianist] Arthur Rubinstein [and] by [conductor] Leopold Stokowski, whom you may remember from Fantasia.”

But while it’s nice to reminisce and draw inspiration from the past, Shapiro acknowledges the importance of advancing the art form and composing new work. And his colleague is the first to say that Shapiro himself is indeed doing just that. “Composers of our time keep the art form alive,” Leibowitz explains. “We cannot sustain a musical world that relies only on the music of the past. As a composer, [Shapiro] does the immeasurably important work of creating new and wonderful music.”

To that end, if he could leave a lasting mark on the New Castle community, Shapiro, who described himself in three words as “giving, loving, and inquisitive,” would like to be remembered for his contributions to the town through his work with the orchestra.

On a personal level, and in a similar vein, he’d like to be remembered as a composer for his score of Frankenstein, which, incidentally, made its world premiere at our very own Jacob Burns Film Center in Pleasantville. Since its premiere, says Shapiro, the score has enjoyed over two dozen performances nationwide “and continues to be asked for from Europe to Australia.”

But, he says, upon reflection, at the end of the day, “I don’t know any composer who doesn’t want to be remembered as a great composer. So [ultimately], I’d love my music to survive me.”

No doubt it will, but in the meantime, The Chappaqua Orchestra isn’t going anywhere anytime soon; in fact, the Town Board recently approved a lease issued last July to utilize Wallace Auditorium at Chappaqua Crossing as a full-time arts and cultural center–and a permanent location for the group. “I’m very happy about the development of the Wallace Auditorium,” says Shapiro, on the subject. “The orchestra now has a home.”

Their “home” will hopefully allow them to play and entertain audiences for years to come–it’s a good thing, too, as Shapiro makes note that these types of groups are unfortunately, not around much anymore. “When I was a kid in the ’50’s, there were 20 orchestras in Westchester,” he shares. “Now, it’s just Yonkers Philharmonic and The Chappaqua Orchestra. Some communities [today] don’t know how to support them.” Also, “Not as many people go to concerts of that kind…. and [because of that] many of us question the future of large ensembles such as symphony orchestras.”

With that in mind, Shapiro “welcome[s] everyone to come to our events and take some time to listen to new music.” And in that same vein of supporting music within our town, he states, “I hope that the work that I’ve done will reach more and more people within the community.” For more information on Shapiro and his work, please visit michaelshapiro.com.

Lover of all things musical, Matt Smith — a proud graduate of Skidmore College — is a regular contributor to the Inside Press, Inc.

Festive CO Fundraiser in Historic Chappaqua Home

Earlier this year: a Chappaqua Orchestra fundraiser took place in a gorgeous music parlor inside the historic Chappaqua home of Frank and Suzanne Shiner.

The program’s “first set” featured:

• String Quartet #1 by Leona Liu

• Dissonance Quartet by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Katsumi Ferguson and Dave Restivo, violins;

Nicole Peragine, viola; Seth Jacobs, cello

• Fantasie for Soprano Saxophone and Piano by J.B. Singelee: Christopher Brellochs, saxophone and Cynthia Peterson, piano

• Meadowlark by Stephen Schwartz: Elizabeth Gerbi, Christopher Brellochs, Cynthia Peterson

A “second set” featured:

• String Quartet in F Major by Maurice Ravel: Katsumi Ferguson, Dave Restivo, Nicole Peragine, Seth Jacobs

• Two songs by Sheldon Harnick and Jerry Bock: Will He Like Me? and I Don’t Know His Name Erin Stewart, Cynthia Peterson

• Stormy Monday Frank Shiner, Christopher Brellochs, Cynthia Peterson

• Duet: That’s All I Ask of You from Phantom of The Opera: Erin Stewart and Frank Shiner

• Bring Him Home from Les Mis, arranged by Cynthia Peterson: Frank Shiner, Katsumi Ferguson, Dave Restivo, Seth Jacobs, Cynthia Peterson