On April 17, as national news headlines warned of an impending crisis and possible war between the U.S. and North Korea, Westchester native and Armonk resident Donald Gregg was one of the few Americans sitting across the table from a North Korean, let alone a high-ranking diplomat. Gregg, the U.S. ambassador to South Korea under President George H.W. Bush, was having lunch with two senior North Korean diplomats and trying to make sense of the latest flare-up in their countries’ animosity.

“We were sort of laughing at the fact that here we are, speaking to each other very civilly,” Gregg recalls, addressing a small group of locals at St. Stephen’s Church in Armonk. “And the news was full of how North Korea was going to be at the center of the next crisis, and the world may come to an end.”

The meeting was nothing new for Gregg, who for decades has been calling for dialogue between the American and North Korean governments.

Gregg’s long career in public service included multiple stints on the peninsula, including as CIA station chief in Seoul from 1973 to 1975 and as ambassador from 1989 to 1993. After retiring from government, he served as chairman of The Korea Society, which promotes cooperation and understanding between Koreans and Americans.

Gregg’s first trip to Pyongyang came in 2002 at the urging of former South Korean president Kim Dae-jung. He has gone five times since, with the latest trip coming in 2014, and has witnessed significant economic growth over that period.

“The people were living better. The conditions were better,” Gregg says of his last visit. “The roads were better, the cars were better, the clothes were better. The body language was better.”

Gregg was in Seoul during some of the tensest moments between the North and the South under the reign of Kim Il-sung, so fear of a sudden attack by the leader of the Kim dynasty is nothing new to him.

But despite the rhetoric coming from Pyongyang, he sees North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, like his grandfather, as a rational actor unlikely to risk his regime through some kind of ill-considered act, like a major attack on the U.S..

“The North Koreans are not suicidal,” Gregg says. “They are not going to use one of their weapons against us, because they know their country would be obliterated.” Even the Kims’ pursuit of nuclear weapons has been undertaken with the regime’s survival in mind, he adds.

“I’ve talked to the North Koreans, and they say ‘We’ve looked at you very carefully. You do not attack people who have nuclear weapons,’” he explains. “That’s the root cause of it. They are scared to death of us.”

The CIA, White House and Two Koreas

Gregg grew up half an hour south of Armonk, in Hastings-on-Hudson. In 1953, he married Margaret Curry, an Armonk native and 1947 Pleasantville High School graduate.

Two days after Gregg’s 14th birthday, Japanese warplanes launched a surprise attack against Pearl Harbor and drew the U.S. into the war already raging across the oceans on each of its shores. In 1945, at the age of 17, Gregg enlisted in the U.S. Army, where he trained as a cryptanalyst. But before he could be sent overseas, World War II ended. Gregg served in the Army until 1947, then attended Williams College in Massachusetts, where he graduated in 1951 with a degree in philosophy.

Though he narrowly missed World War II, he would leave a mark on the four-and-a-half decade Cold War that followed. He joined the CIA in 1951 and served in Japan and Vietnam, learning to speak Japanese fluently. In 1973 he was sent to Korea, where he served as station chief. There, he helped stop torture by his Korean counterparts and played an important role in the rescue of Kim Dae-jung, who went on to become South Korea’s president.

Gregg worked at CIA headquarters from 1975 to 1978 and then as an Asia policy specialist for the National Security Council under the Carter administration. During the Reagan presidency, Gregg was director of the NSC’s Intelligence Directorate before being appointed Vice President Bush’s National Security Advisor.

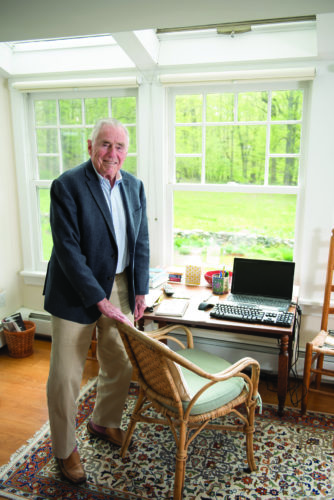

When Bush became president, Gregg was appointed ambassador to South Korea. Forty years after joining the CIA in the early years of the Cold War, Gregg now played a role in its end. After Bush’s lone term ended, the Greggs returned to New York and in 1995 moved to Armonk, with Don chairing The Korea Society. He began teaching a course at Williams, looking to get top students interested in public service. In 2014 he published a memoir, titled Pot Shards: Fragments of a Life Lived in CIA, the White House, and the Two Koreas, about his experience.

Gregg has been active locally as well, meeting every month with Armonk neighbors to discuss history, politics and current affairs. “Don has had an immense contribution on the global stage, but he has had an immense contribution locally as well,” says Rev. Nils Chittenden, the Rector of St. Stephen’s, where Gregg is an active congregant. “We as a congregation really appreciate and recognize that we are in the presence of someone that has really had a huge effect on shaping world history.”

A ‘Very Different’ President

Gregg has met eight American presidents. He also met the current president, and though their brief meeting took place years before Donald Trump would seriously consider any political run, Gregg’s view of the 45th president remains broadly the same. “I don’t like Trump,” he says bluntly. “He and I are very, very different people.”

Gregg holds out hope that Trump will change course on North Korea and move away from the escalating rhetoric seen during the first months of the administration. He notes some positives, such as the appointment of HR McMaster as National Security Advisor.

But just as Americans find it difficult to understand Kim Jong-un, Koreans have trouble making sense of Trump’s approach.

“We neither like nor understand the North Koreans,” Gregg wrote in a letter submitted in April to The New York Times, “and fill our gaps of ignorance with prejudice that prevents us from thinking vicariously about Pyongyang, its concerns and policy objectives.”