Audrey Birnbaum’s father, Jack Schwersenz, was determined that the story of his childhood escape from Nazi Germany be passed on to future generations. So in his 70s, he typed it all out… every single grueling detail, amounting to 350 pages. “But I couldn’t get past the first chapter,” recalled Audrey. “It was too tedious, too detailed, too cumbersome to read.” So she stored it away in the attic of the Briarcliff Manor home where she and her husband raised their three children.

When Jack died about 15 years later, she needed some details to flesh out his eulogy. Having recently broken her leg, she practically crawled up the steep attic stairs to retrieve the manuscript. “Then, as a I skimmed it with tears in my eyes, I realized just how rich it was. It was a story that had to be told. But in my dad’s form, it still seemed like nothing more than a testimony that might be of interest to a Holocaust museum,” Audrey said. “A few years later, when the Pandemic hit and I had retired from my 35-year career as a pediatric gastroenterologist, I decided to see if I could make it readable.”

And that she did…

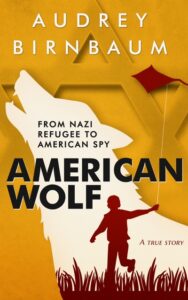

The result, American Wolf: From Nazi Refugee to American Spy, is the true story of a Jewish boy’s childhood in Berlin, his riveting escape in 1941 with his parents aboard the Navemar (the Spanish freighter that carried about 1,120 European Jewish refugees to the United States in overcrowded and unsanitary conditions), the challenges the family faced as immigrants in New York City, and his return to Germany in his 20s as an intelligence officer for the U.S. Army.

Published in October 2023, the book has garnered rave reviews from readers, while Audrey has spoken at numerous local and national forums and has been interviewed on dozens of podcasts and news shows. American Wolf: From Nazi Refugee to American Spy also was named a 2023 National Jewish Book Award finalist for Holocaust Memoirs.

“By narrating this true story in the first person, Audrey Birnbaum deftly transports the reader to 1930s Berlin, and we are at once immersed in a family drama during the rise of Hitler,” wrote one reviewer. “This is a story of determination, survival and resistance that is as relevant today as at any time in the last three generations.”

Other reviewers praised Audrey’s writing style as engaging, amusing and witty, and applaud her ability to bring the characters’ stories to life. One could easily assume that she is a professional writer. In fact, this is her first book, although she did briefly consider a career in journalism while a student at Stuyvesant High School in New York City.

She and her older sister grew up in Flushing, first in the same one-bedroom apartment that her father and grandmother lived in when they moved out of Washington Heights, their port of entry when they arrived in New York City from Germany. Eventually, they “literally pushed” their furniture a half block away to a larger apartment, where her mom still resides.

As young children, she and her sister did not quite fit in with the other kids, often feeling like outcasts and becoming victims of bullying. “We ate differently, dressed differently, listened to classical music, and only watched public television. My father raised us as if we were German,” she recalled, noting that her lunchbox typically contained a liverwurst sandwich rather than PB&J. “He also developed from his war experience a pathological fear of spending money. We wrote down every penny we spent. Everything was measured – food, money, toilet paper, phone calls. If we went on a class trip, we didn’t have spending money to buy a souvenir the way other kids did.”

While her childhood was in many ways similar to that of other immigrant children, her father’s history and approach to life had a profound impact. “My sister and I were immersed in his past very early on – he loved to talk about being German and about his great escape on the last train out of Germany,” Audrey recalled. “He was obsessed with the Holocaust, and we watched documentaries about it from the time I could remember. While other kids talked about their trips to Disneyland, in a perverse way, I tried to make myself important by saying my father was a Holocaust survivor.”

Jack also passed on to his daughters a strong work ethic. After working as a CPA, he eventually started publishing out of their apartment a monthly newsletter for accountants. And since he refused to hire a staff, it became a family business, with Audrey, her sister and mother helping with typing, editing, collating and stuffing envelopes.

Since it was understood that they could not afford for the girls to go to college outside of New York, Audrey’s career path was sealed when she was accepted into the six-year Sophie Davis Biomedical Education Program/CUNY School of Medicine. She started practicing medicine at the age of 22.

Since it was understood that they could not afford for the girls to go to college outside of New York, Audrey’s career path was sealed when she was accepted into the six-year Sophie Davis Biomedical Education Program/CUNY School of Medicine. She started practicing medicine at the age of 22.

“When you grow up in a house where work was valued and leisure was frowned upon, it’s very hard to be leisurely as an adult,” she said. “Even when I stopped working as a physician, somehow I was always busy. I’m always in motion,” said Audrey who enjoys singing and reading and has started writing her second book.

“I also love to fix things, which is partly what drove my determination to re-write my father’s memoirs,” she said. “I was also compelled by a sense of obligation to him.”

She dove into researching historical facts and long-lost family members to fill in gaps in her father’s manuscript. And once she started writing, she couldn’t stop – creating several drafts as she experimented with different styles and approaches.

Although Jack often shared with his daughters details about his childhood in and escape from Germany, he rarely spoke about the hardships he and his family faced once they arrived in New York City. Like so many other immigrants, his family gave up comfortable lives for the often harsh realities of starting over, such as becoming menial laborers and living in roach-infested apartments. He also didn’t divulge much about his experiences when he was drafted during the Cold War and stationed in Germany, where as a native speaker he became a valuable spy.

His memoirs reveal all this, as well as Jack’s struggle with figuring out who he was. “In Germany, he was rejected for being a Jew. When they got here, he faced both antisemitism and anti-German sentiments,” Audrey said. “He tried to fit in as an American, but that wasn’t easy. This is how the title American Wolf came about.”

Jack’s given name was Wolf, but on his first day of school in New York City, the assistant principal encouraged him to change it to avoid being teased by other children.

“This is not only a story of rejection by one country and acceptance by another, but also a parallel story about discovering one’s identity – about self rejection and self acceptance,” Audrey said. “When you are considered a lower-class citizen and told that you are worthless, you absorb all of that into your psyche – so you have to go through a process of self acceptance. The book ends when my dad married my mom… when he ultimately found love and acceptance.”